How Non-Muslim Communities Responded to Muhammad’s Message (Historic Accounts)

When Muhammad began preaching his message in early seventh-century Arabia, the region was home to many religious groups and traditions. His call for one God brought strong reactions from different communities. Some groups pushed back, others watched with caution, and a few found opportunities for dialogue.

Looking at non-Muslim responses helps us see how early Islam fit into the larger social and religious setting. Each community weighed Muhammad’s message against their own beliefs and interests. This shaped not only the challenges he faced but also the moments of cooperation and peace. Understanding these early encounters helps us grasp why the story of Islam’s beginning is about much more than its first followers.

Reactions of Pagan Arabs in Mecca

When Muhammad began sharing his message of strict monotheism, the city of Mecca was buzzing with trade, tradition, and deep pride in its tribal roots. Most locals belonged to the Quraysh and other pagan Arab tribes, who saw their city as a religious and commercial center. For these groups, Muhammad’s message didn’t just challenge their beliefs. It struck at the heart of Meccan identity, customs, and even their economic security.

Initial Opposition from the Quraysh and Other Pagan Tribes

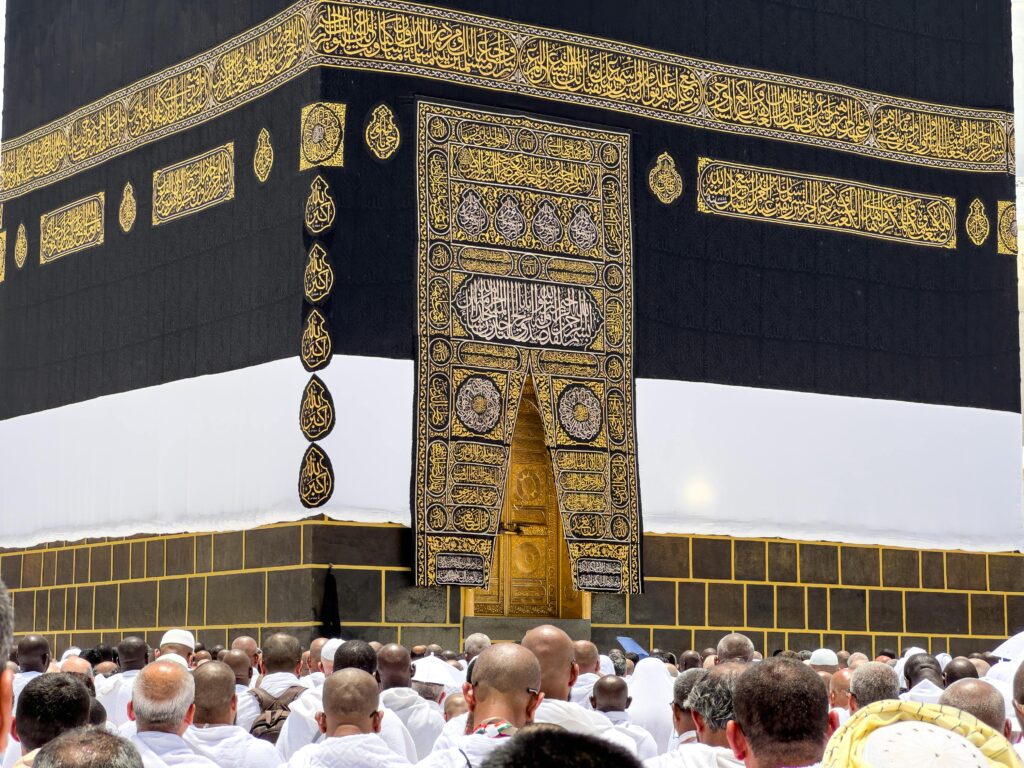

The first listeners to Muhammad’s call were not distant strangers. They were neighbors, family, and business partners. The Quraysh, who managed the Kaaba and its trade-driven pilgrimages, watched as this new message grew. From their view, Islam threatened old alliances and daily routines. The Quraysh feared that abandoning old gods would upset the status quo, hurt Mecca’s reputation as a sacred city, and cut into their profits from visiting tribes.

Early on, some mocked Muhammad, doubting his motives. Others worried about new rules upending old freedoms. For those whose social standing relied on tradition, Islam’s message felt like a personal challenge.

Social Pressure and Persecution

Efforts to silence Muhammad and his followers quickly moved beyond words. Social pressure mounted. Families threatened members who showed interest in Islam. Some new Muslims lost the protection of their clans, making them easy targets for public insults or even worse. According to documented sources, many faced long stretches of intimidation, and in some cases, outright violence. These efforts included:

- Cutting off business dealing with Muslims

- Public shaming and physical abuse

- Pressure on influential family members to turn against converts

Even so, a handful of followers stuck with Muhammad, drawn by the promise of a new kind of community.

The Economic Boycott

As Islam gained a small but devoted following, the Quraysh coordinated a harsh economic boycott. This action targeted Muhammad’s clan, the Banu Hashim, aiming to squeeze the community into giving up their support. The boycott meant:

- No trading with or marrying Muslims

- Refusing to sell food and supplies to the Banu Hashim

- Isolating Muslims from most business and social contacts

For nearly three years, this boycott pushed the early Muslims into severe hardship, with reports of near-starvation for some families. Yet, the boycott also brought public sympathy from a few fair-minded Meccans who felt the measures had gone too far. For details and first-hand accounts of what the early Muslims endured, read about the persecution of Muslims by Meccans.

Roots of Hostility: Religion, Power, and Social Order

Why did the pagan Arabs react so strongly? Several factors fueled their hostility:

- Social Customs: Islam’s call for one God cut against the grain of everyday rituals, festivals, and family honoring of old gods.

- Tribal Leadership: Many leaders feared Islam would weaken their authority and leadership structures.

- Economic Interests: Control of the Kaaba and religious pilgrimages attracted wealth. New beliefs threatened these profits.

- Fear of Change: For any society, rapid change provokes anxiety. In Mecca, old traditions acted as a glue for the social order.

For a deeper dive into why the Quraysh felt so threatened by Muhammad’s message, see this analysis on Meccans’ opposition to Muhammad.

The early period in Mecca was marked by tension and difficulty, but it also set the stage for a new kind of community, bound by faith instead of tribe alone. Through both hardship and resilience, the reactions of pagan Meccans became a turning point in Muhammad’s mission.

Jewish and Christian Responses in Medina and Beyond

After migrating to Medina in 622 CE, Muhammad faced a religiously diverse community—Jewish tribes, polytheists, and a smaller Christian presence. Their reactions were mixed, ranging from cooperation to skepticism. Some Jewish groups questioned his prophetic claims, while Christian communities often found common ground in shared monotheistic principles. Two key developments defined these early interactions: the Charter of Medina and protections for Christian groups like St. Catherine’s Monastery.

The Charter of Medina: Early Pluralism

The Charter of Medina wasn’t just a treaty. It was a bold experiment in coexistence. Drafted shortly after Muhammad’s arrival, it united warring Arab clans, Jewish tribes, and early Muslims under a shared legal framework. The charter:

- Recognized Jews as part of the ummah (political community) with equal protection.

- Allowed each group to follow its own laws in personal and religious matters.

- Mandated mutual defense against external threats.

- Prohibited alliances with hostile forces, like the Quraysh of Mecca.

For its time, this was radical. The idea that faith groups could coexist under a single civic structure broke from tribal loyalties. Yet tensions arose. Some Jewish leaders doubted Muhammad’s prophethood, seeing it as incompatible with their scriptures—a rift that later led to conflict when alliances soured. Still, the charter set a precedent for religious pluralism rarely matched in early medieval societies. Learn more about its historic clauses and interpretations.

Special Protections for Christian Communities

Christian groups fared differently, often securing direct treaties with Muhammad. One famous example is the Ashtiname (sacred covenant) granted to the monks of St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, promising:

- Protection from attacks and destruction of property.

- Exemption from military service.

- Freedom to practice Christianity without interference.

Similar agreements were made with Najran’s Christians. Here, Muhammad opted for diplomacy—imposing no forced conversions, only a modest tax (jizya). His letters to Christian leaders emphasized respect for clergy and churches, framing them as “People of the Book.”

Why this distinction? Unlike the Jewish tribes of Medina, Christian communities often lived outside Arabia. They posed no political threat, and their theological differences (like the Trinity) sparked debates but rarely violence. The Ashtiname and other treaties showed pragmatism—secure allies, ensure safe travel for traders, and avoid unnecessary conflict. For a deeper look at these covenants, see analysis of Muhammad’s Christian treaties.

While relations weren’t always perfect, both examples—the Charter’s shared citizenship and the Ashtiname’s specific protections—reveal nuanced strategies for handling religious diversity in early Islam.

Foundations of Tolerance: Non-Muslim Rights under Muhammad

When Muhammad established Islamic rule in Medina, he faced a critical question: how to govern a religiously diverse society. The answer came through the concept of ahl al-dhimma (protected people), a legal framework granting Jews, Christians, and later Zoroastrians specific rights and protections under Islamic law. This wasn’t just tolerance. It was a binding contract between the Muslim state and its non-Muslim citizens.

Who Were the Dhimmi and What Rights Did They Have?

Ahl al-dhimma (often shortened to dhimmi) referred to non-Muslims who accepted Islamic rule while maintaining their faith. In exchange for paying a poll tax (jizya), they received:

- Legal protection: Guaranteed safety of life, property, and places of worship.

- Religious freedom: The right to practice their faith, build churches or synagogues, and follow their own family laws.

- Autonomy in internal matters: Jewish and Christian communities could resolve disputes within their religious courts.

- Exemption from military service: Though they were protected by the Muslim state, they didn’t have to fight in its armies.

The jizya wasn’t just a tax. It functioned as a substitute for the zakat (alms tax) paid by Muslims, acknowledging a different civic role while ensuring protection. Early accounts show Muhammad enforcing strict penalties for harming a dhimmi, making their safety a core principle. For a deeper dive, explore the legal distinctions between Muslims and dhimmis.

Responsibilities and Limits

Protection came with conditions. Dhimmis had to:

- Pay the jizya annually (often a modest sum based on income).

- Avoid proselytizing or publicly insulting Islam.

- Refrain from fighting alongside enemies of the Muslim state.

Though they couldn’t hold high political or military offices, many thrived as doctors, merchants, and scholars. Some restrictions, like prohibitions on building new churches in certain areas, varied by ruler. Yet overall, the system offered stability in an era where religious minorities elsewhere faced expulsion or forced conversion.

Why This Approach Mattered

Muhammad’s policies weren’t just pragmatic. They reflected a broader principle: monotheistic communities deserved respect. Unlike pagan groups, Jews and Christians were Ahl al-Kitab (People of the Book), sharing Abrahamic roots with Islam. This recognition allowed for:

- Economic cooperation: Jewish traders in Medina and Christian farmers in Syria continued their work without disruption.

- Cultural exchange: Early Muslim scholars consulted Jewish rabbis and Christian monks on theology and law.

- A model for later empires: The Ottoman millet system borrowed from this framework, granting autonomy to religious groups.

But it wasn’t perfect. Tensions flared when alliances broke down, as with some Medina Jewish tribes accused of aiding the Quraysh. Yet even then, punishments were typically exile, not mass violence—a contrast to medieval Europe’s treatment of minorities. For more on early legal debates, see this analysis of dhimmi status.

By formalizing rights for non-Muslims, Muhammad set a precedent. The dhimma system showed that Islamic rule could accommodate diversity without demanding assimilation—an idea that shaped interfaith relations for centuries.

Conclusion

The early responses to Muhammad’s message reveal a complex mix of resistance, negotiation, and cooperation. Pagan Meccans feared disruption to their traditions, Jewish communities in Medina engaged in both alliances and conflicts, and Christians often found protections under Islamic rule through treaties like the Ashtiname. These interactions weren’t just about faith. They shaped politics, economics, and social structures in ways that still echo today.

What can we learn? Religious pluralism isn’t a modern invention. Muhammad’s policies—whether the Charter of Medina or dhimmi protections—set early precedents for coexistence. While tensions existed, the framework for tolerance was there.

Want to explore more? Compare these historic examples with interfaith dynamics in your own community. How do societies balance belief and belonging? The past offers clues, but the conversation continues. Drop your thoughts below or share this piece with someone who enjoys history’s messy, human stories.