Quranic View of Women’s Equality (Understanding Muslim Female Rights Today)

When people talk about women’s equality in Islam, the Quran often comes up as the first source for guidance and debate. For Muslims, what the Quran teaches about women’s rights shapes daily life, beliefs, and community rules. For non-Muslims, understanding these teachings helps bust common myths and build informed conversations about faith and gender.

This post covers the history behind Muslim women’s rights, key Quranic verses, different approaches to interpretation, and what these lessons mean today. It also looks at ongoing efforts to reform laws and customs and the challenges faced along the way. If you want to understand the roots, reality, and future of women’s equality in Islam, you’re in the right place.

Watch a trusted resource: Understanding Women’s Rights in the Quran: Truth vs. Misconceptions (YouTube)

Historical Context of Women in the Quran

To understand women’s rights in the Quran, we need to see where society started. Looking at the customs before Islam and the reforms that followed helps explain why the Quran’s teachings were so significant for women.

Pre‑Islamic Arab Society

Before the arrival of Islam in 7th-century Arabia, women faced many harsh realities. Their status in society was tied to family or tribal honor. Most did not inherit property and had little control over their own lives. Marriages were arranged without their consent, and some women were treated as inherited property themselves.

A practice that still shocks today is female infanticide. In some tribes, newborn girls were sometimes buried alive, seen as a burden on the family. This was not universal, but it was common enough to mark an era of insecurity for girls’ survival. Reputable historians and sources, including detailed essays on the subject, confirm this tragic part of social history Women in Pre-Islamic Arabia.

Women had little say in public life. Decisions happened in male circles, with women left out of legal, political, and economic matters. Daughters almost never received inheritance; property usually went to male relatives. Social status for many women depended on their relationships as mothers, daughters, or wives. Research on Women in pre-Islamic Arabia highlights these limitations across the region.

- Common realities for women in pre-Islamic Arabia included:

- Limited or no inheritance rights

- Marriages arranged without their voice

- Lack of personal agency in economic life

- Social expectations to be obedient and mostly invisible in public

Awareness of this context shows the weight of what would come next.

Revelation and Early Islamic Reforms

With the Quran’s revelation, change began. It didn’t happen overnight, but many basic rights for women first found strong, clear support in these early verses.

Spiritual Equality: One of the first messages was that men and women are spiritually equal. The Quran repeatedly speaks to “believing men and believing women,” placing their moral worth and accountability on the same footing. Surah An-Nisa opens with this clear idea Women in the Quran: A Nuanced Exploration of Surah An-Nisa.

Inheritance and Property: The Quran gave women the right to inherit, something nearly unheard of in pre-Islamic customs. Verses like An-Nisa 4:7, 4:11, and 4:32 directly address both men and women, arranging for assigned shares and fairness. Surah An-Nisa – 1-176 outlines these early reforms, where both sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, receive specified inheritance.

Consent in Marriage: The Quran establishes the need for valid consent and fair treatment in marriage. Forced marriage is discouraged, and a woman’s permission must be considered.

Education: The very first revelation to Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) centered on seeking knowledge for everyone. The command “Read!” in Surah Al-‘Alaq (96:1-5) embraced both women and men Surah Al-‘Alaq 96:1-5 – Towards Understanding the Quran. This set a tone that all believers, regardless of gender, had a duty to learn and grow.

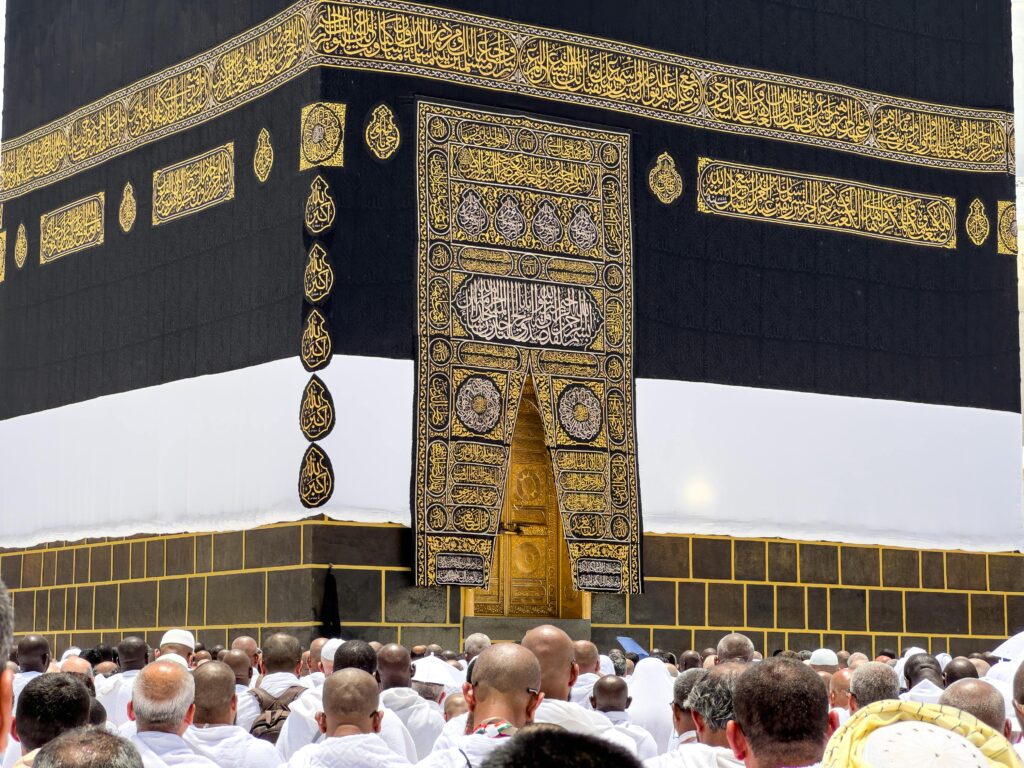

Photo by Prime Media Photography

These early reforms shifted the baseline for what women could expect. Suddenly, women inherited property, chose their marriage partner, received education, and had spiritual dignity affirmed in scripture.

Tables or lists summarizing these changes highlight just how far the original message went compared to what came before:

| Issue | Pre-Islamic Practice | Quranic Reform |

|---|---|---|

| Inheritance | Few or no rights | Clear shares for women and men (An-Nisa 4:7, 4:11, 4:32) |

| Consent in Marriage | Arranged, little female input | Consent required, women’s will respected |

| Public Voice | Minimal influence in society | Encouraged participation, especially in early community |

| Education | No priority for women | First revelation urged knowledge-seeking for all |

These steps didn’t erase every barrier overnight, but they charted a new path for women in Muslim communities. Today’s debates and reforms often return to these original verses, showing just how important they remain.

Key Quranic Verses on Gender Equality

The Quran shares a clear message about men and women having equal value, especially where it matters most: the soul and the law. These verses are often quoted to show how Islam defines dignity and rights for women. Let’s look closer at the core Quranic verses that set up the foundation for equality in faith and daily life.

Spiritual equality: piety and moral worth

Some of the strongest statements about gender equality in Islam relate to the spiritual side of life. The Quran pushes believers to rise above labels like “man” or “woman” and focus instead on who you are as a person.

- Surah Al-Ahzab 33:35 stands out for its clear language. In this verse, men and women are listed side by side for all the values that matter: faith, honesty, patience, humility, charity, fasting, modesty, and remembering God. The verse drives home that every person has their worth measured by devotion and good character, not gender. You can read a range of respected translations here: Surah Al-Ahzab 33:35.

- Surah Al-Hujurat 49:13 is just as direct. Here, God addresses all people and says He created humans as different men and women, tribes and families, not for us to fight about who is better, but to know and respect each other. What counts is piety, not gender, race, or background.

These verses make it simple: The most honored before God is the most moral and God-conscious. Gender has nothing to do with spiritual rank. This message set a new social standard in a world where women were often ranked lower by default.

Legal rights: inheritance, ownership, testimony

Equality doesn’t stop at spiritual status. The Quran also set rules that gave women clear legal rights, many of which were unseen in other societies at the time.

- Inheritance Rights (4:7, 4:11, 4:32): Before Islam, women rarely inherited. The Quran gave women a definite share from what parents and relatives leave behind, making it law that women cannot be cut out. Surah An-Nisa 4:7 states, “For men is a share of what the parents and close relatives leave, and for women is a share…” Surah 4:11 and 4:32 outline how these shares are calculated and protect against anyone denying a woman’s due. The Tafsir of Surah An-Nisa breaks down these rules for both men and women.

- Ownership: The Quran makes clear that women have the right to own property. Whether a woman gets property by inheritance, work, or gift, it stays her own asset, not her husband’s or father’s.

- Testimony: Verses covering testimony are often debated. The Quran makes practical laws for giving testimony in financial dealings, aiming to make sure nothing is lost or forgotten. While different rules appear for different kinds of legal cases, it’s clear that women’s voices are part of the legal process.

Here’s a quick summary in table form for easy scanning:

| Right | Quranic Reference | What It Means for Women |

|---|---|---|

| Inheritance | 4:7, 4:11, 4:32 | Women are guaranteed a share of inheritance |

| Ownership | 4:32 | Women can own and control their property or wealth |

| Testimony | 2:282 (for financial contracts) | Women’s testimony is included in detailed legal rules |

For more direct text and explanation, the translation and commentary on Surah Al-Ahzab provides thoughtful context about women, rights, and law.

These verses were a turning point; they built a framework that protected women’s interests and put their dignity into written law. The effect was more than just symbolic—these guidelines shaped families, economics, and justice for generations.

Interpretive Approaches: Traditional vs. Feminist

The way people read and understand the Quran deeply shapes beliefs about women’s rights in Islam. Interpretations (or “exegesis,” known as tafsir) are not set in stone; they reflect the mindset and experience of the scholars who wrote them. Looking at both classical and feminist approaches side by side shows how much the method, questions, and context matter.

Classical exegesis and its limits

Early Islamic scholars came from cultures where men held most power. These scholars worked within traditions and social rules that influenced how they saw Quranic verses about women. As a result, many classic commentaries often justified or maintained men’s authority over women.

Some patterns stood out in classical tafsir:

- Social customs set the tone: If women in that scholar’s time faced restrictions, the tafsir often reflected those limits. Scholars rarely challenged the norms they lived under, and these views carried into religious rulings.

- Patriarchal readings were common: Many interpretations focused on men’s leadership in the family and public life. Verses about men and women were explained in ways that often downplayed female agency or suggested women should follow men.

- Literal over contextual reading: Early scholars often took verses at face value, relying on stories and traditions rather than historical or cultural context.

Academic reviews offer more on these trends. See a full analysis at Women and Tafsir – Islamic Studies and research discussing how gendered readings shaped expectations for women in Islamic societies Classical Qurʾanic Exegesis and Women (PDF).

This approach created solid boundaries for women’s roles and rights, linking them more to tradition than the text’s possible meanings. It’s hard to ignore that many limitations on women came not from the Quran itself but from how it was explained.

Modern feminist ijtihad

Contemporary scholars, many of them women, use different skills and ask new questions when interpreting the Quran. This movement is often called feminist ijtihad (independent reasoning). Instead of sticking to old answers, these thinkers look for the goals (maqâṣid al-sharî‘ah) behind Quranic law and the message as a whole.

Here’s how feminist ijtihad works:

- Context matters: Feminist scholars study the time, place, and reasons behind each verse. They check how social customs from centuries ago affected early readings and ask: Is that what God’s message really aimed to continue, or was it meant to improve society step by step?

- Focus on the objectives (maqâṣid al-sharî‘ah): These interpreters see God’s law aiming for justice, compassion, and human dignity. If a verse seems to limit women, they check if that fits the bigger goals of the Quran, especially when other verses call for balance and fairness.

- Equality as a principle: Feminist scholars highlight verses teaching equal worth, like those on mutual rights and responsibilities between men and women. They argue that the spirit of the Quran supports equality.

Some well-known scholars and examples include:

- Amina Wadud, whose work on Qur’an and Woman emphasizes inclusive and fair interpretations.

- Asma Barlas, who argues that restrictive readings often come from patriarchy, not from the text itself.

- New research continues to push against one-sided views, offering broader ways to understand women in Islamic law Reframing Quranic Exegesis through the Lens of Gender.

Through feminist ijtihad, the focus shifts toward the Quran’s deeper goals: justice, uplift, and the dignity of every person, female or male. These approaches challenge readers to ask new questions and rethink what true equality can look like for Muslim women today.

Practical Implications for Muslim Women Today

The teachings of the Quran are not kept in dusty books—they live on in how real people make choices today. For Muslim women, the principles of spiritual equality and legal rights shape experiences in schools, workplaces, homes, and courts. The day-to-day impact of Quranic ideals shows up in education, jobs, and the personal status laws that guide marriage and family life.

Education and employment

Knowledge-seeking isn’t just a nice idea in Islam—it’s a duty for every believer. The Quran sets a clear standard by making education a right, not a privilege. Surah Al-‘Alaq was revealed with the powerful command to “Read!”—a call intended for women and men alike. Prophetic sayings support this, urging all Muslims to pursue learning from the cradle to the grave.

But how does this message play out in daily life today? Muslim women’s access to education varies widely, depending on the country and local customs. In countries like Saudi Arabia, women now outpace men in university enrollment and graduation rates. In India, recent data shows that 79.5% of Muslim women are literate, close to the national average, but just 5% make it to higher education, compared to 8% for the broader population. In North India, the situation is more complicated, with only 49% of Muslim girls enrolling in government schools and a staggering 88% of adult Muslim women remaining illiterate. See the contrasting trends in this 2024 review of Muslim women’s education in India and learn about barriers and progress.

Globally, young Muslim women are closing the gender gap. A Pew Research Center study shows that younger generations have much more formal education than older ones, sometimes even surpassing their male peers The Muslim gender gap in educational attainment is shrinking. Yet, stark contrasts remain—especially in places like Afghanistan, where official restrictions keep 1.4 million girls out of school entirely, violating the fundamental Islamic mandate for learning Taliban ‘deliberately deprived’ 1.4 million girls of schooling.

Entering the workforce, Quranic teachings affirm each woman’s right to own property, earn income, and work outside the home. Islamic law recognizes women’s earnings as exclusively theirs and stresses fair wages. Countries like the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia have seen more Muslim women in fields like business, healthcare, and STEM. Yet, challenges such as wage gaps, workplace discrimination, and cultural resistance still exist.

When schools and employers follow Quranic values, they create space for Muslim women to learn and thrive. The visible success of Muslim female scientists, entrepreneurs, and scholars shows that faith-based equity can be a springboard, not a ceiling.

Family law and personal status

Family life touches every Muslim, and the way marriage, divorce, and custody are handled depends heavily on local application of religious laws. The Quran was bold for its time, requiring women’s active consent in marriage, acknowledging their right to request divorce (khula), and confirming women’s claim to child custody—especially in a child’s early years.

In practice, national laws vary widely across the Muslim world:

- Marriage consent: In places like Indonesia and Tunisia, courts require proof that women agree to their marriage. In South Asia, arranged marriage with family negotiation remains common, but Islamic law is increasingly used to challenge forced unions.

- Divorce rights: Some countries (including Egypt and Morocco) have updated laws making divorce fairer for women. The Moroccan Family Code (Moudawana), for example, lets women file for divorce easily and claim financial rights after separation.

- Custody rules: While the Quran supports mothers’ claims to custody, in some societies, local custom or law gives preference to fathers after a certain age. Tunisia and Turkey have pushed toward more gender-balanced custody laws, but practice can lag behind policy.

Progress often faces social headwinds. In India, recent court cases have put female consent and financial security at the center of legal debates. Campaigns to end “triple talaq” (instant divorce) in South Asia have succeeded in some countries, reflecting a return to Quranic justice and due process for women.

These advances show both promise and gaps. Where the Quran’s spirit of fairness guides local laws, women’s dignity and agency shine. Where tradition or politics interfere, reformers often use Quranic teachings to make the case for stronger rights.

In short, Muslim women today navigate a complex world where the letter and spirit of the Quran are alive in modern discussions on education, work, marriage, and motherhood. Their stories—whether small wins or calls for change—prove that equality isn’t just in sacred text. It’s also being written into daily life, one decision at a time.

Challenges and Opportunities for Reform

Muslim women seeking equality in faith and daily life face real hurdles alongside new open doors for progress. While the Quran sets a bold foundation, resistance from traditionalists and slow-moving legal systems often blocks change. At the same time, civil society groups, global agreements, and interfaith partnerships work to build a stronger base for women’s rights rooted in both scripture and universal values.

Resistance from conservative scholars

In many regions, some religious scholars push against gender-equal readings of the Quran. Their arguments often come from tradition, social norms, or fear of losing authority. These scholars claim:

- Divinely mandated roles: They interpret certain verses as setting fixed, separate duties for men and women, often using these to reject shared leadership or equal legal rights.

- Change as “innovation”: They label reformist readings of the Quran as forbidden innovations, framing new ideas as threats to Islamic identity.

- Patriarchal customs baked in: Many classical commentaries align with the social order of their day. As a result, readings that favor male authority seem “normal” and become hard to question.

This resistance can persist for generations, especially in communities where religious leaders set the tone for both public policy and private life. Scholars often shape legal codes and cultural expectations, reinforcing ideas that restrict women even when these limits go beyond scripture.

For a look at these challenges and why they stick around, see Women and the Qur’an: Feminist Interpretive Authority?. Researchers also point out that efforts to reinterpret the Quran face backlash when seen as deviating from traditional views (Realizing Inclusive Interpretation in the Modern Era).

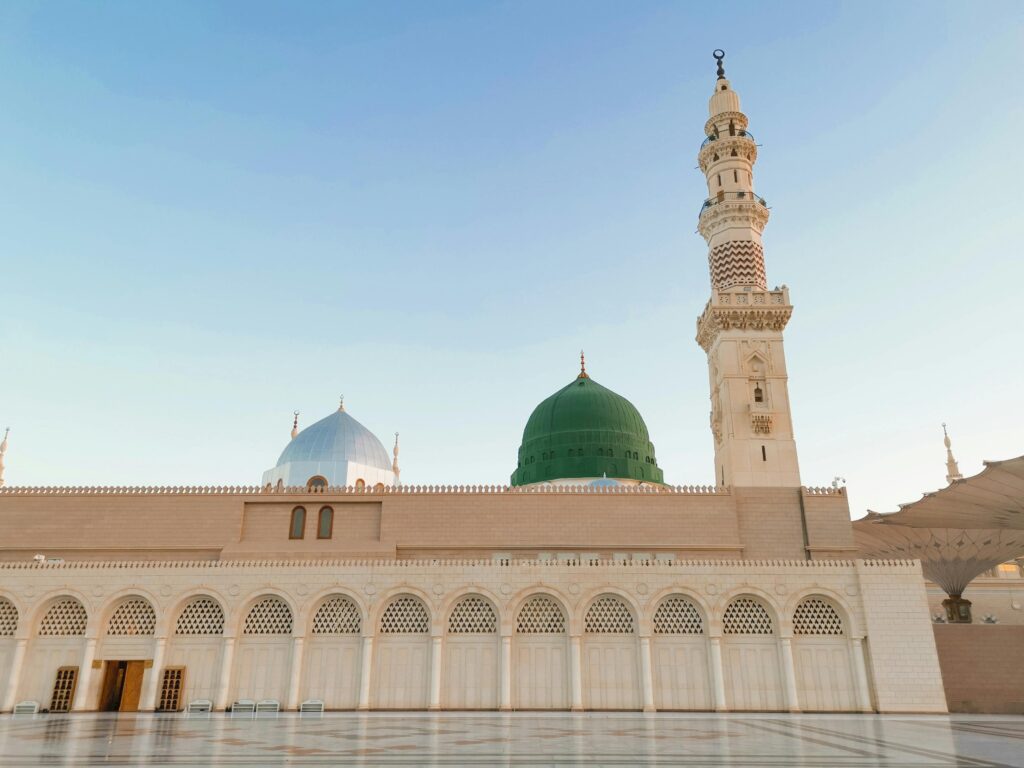

Photo by Sima Ghaffarzadeh

This photo reflects one way women challenge such barriers, using public protest to speak for gender justice.

Role of civil society and international frameworks

In the face of slow change from within, reform often comes from the ground up. Civil society groups, NGOs, and global frameworks work together to push for women’s rights that match both the Quran’s principles and international standards.

- Civil society advocacy: Local women’s groups and rights organizations lead grassroots campaigns, train leaders, and educate communities about Islamic teachings that favor gender fairness.

- International agreements: The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) helps Muslim-majority countries review and update unjust laws. CEDAW’s review committees, for instance, have urged changes to inheritance rules and marriage laws in several Muslim countries.

- Interfaith dialogue: These forums bring together Muslims and people of other faiths to discuss shared values. They tackle stereotypes and build support for women’s rights, showing how justice and equality fit with both faith and global ethics.

Table: Examples of Reform Pathways

| Pathway | Example |

|---|---|

| NGO advocacy | Local groups in Morocco played a key part in amending the Moudawana (family code), giving women more rights in marriage and divorce. |

| CEDAW-based legal review | After CEDAW recommendations, Tunisia updated its inheritance and marriage laws to limit discrimination. |

| Interfaith partnerships | Dialogues in Indonesia have led to joint campaigns on domestic violence, bringing Muslim, Christian, and secular groups together. |

Stories of impact come from across the Muslim world. Read more on how Islamic law, CEDAW, and civil society interact, and see real-world models of Muslim feminist legal reform.

Change may feel slow when old habits run deep, but every new court ruling, peaceful protest, and cross-faith talk opens doors. Reform rooted in both scripture and universal rights gives hope that women’s equality will move from hopeful words to daily reality.

Conclusion

The Quran’s core message treats men and women with equal worth, laying the foundation for gender justice. Across time, open and context-aware readings have shown that the spirit of the Quran welcomes fairness and respect for all believers. It’s clear that progress for Muslim women grows when interpretation honors both faith and the changing world.

If you care about equality within authentic religious values, support those who engage with scripture using both tradition and new insight. Back organizations, teachers, and scholars who advocate for faith-based justice. Your voice, learning, or donation can help shift debates from old habits to genuine fairness.

This is an ongoing journey fueled by study, reflection, and community action. Thank you for reading and staying curious. Let’s keep working together toward understanding, respectful dialogue, and a future where everyone’s dignity stands protected. If something here sparked your interest, share your view or recommend another good resource—everyone’s insight adds value.